Women arbitral practitioners came of age in the 21st century. Yet it was only 100 years ago that women were first allowed to become lawyers in the UK. This December the UK celebrates the centenary of the strangely worded piece of legislation entitled the “Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919”.

Women arbitral practitioners came of age in the 21st century. Yet it was only 100 years ago that women were first allowed to become lawyers in the UK. This December the UK celebrates the centenary of the strangely worded piece of legislation entitled the “Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919”.

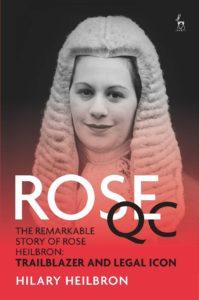

Rose Heilbron, my mother, was a barrister and one of the pioneers of this progression, who became a famous advocate in the middle of the last century with a string of firsts in the profession to her name, including first woman Queen’s (then King’s) Counsel and first female Senior Judge.

To coincide with this centenary, “Rose QC”, the biography I wrote of her remarkable life, has just been re-issued in paperback. It chronicles the struggles she and other women had in those early days, her exhortations in favour of equality for women and how she became a trailblazer and legal icon.

There are several events scheduled to coincide with this centenary. The 100 Year’s Project, a compendium of female lawyers’ achievements, is spearheading the celebrations. It can be found at https://first100years.org.uk/ with my mother’s face as the backdrop.

The idea, even 70 years ago, of women in the UK practising commercial law or international arbitration or acting as international arbitrators was a bridge too far and it was only later in the last century that women began to flex their muscles in these directions.

100 years ago the world was a very different place: it was only a year after the ending of the First World War and the partial enfranchisement of women in the UK, namely those over 30. Yet, women remained strange beings in legislators’ eyes and, for example, in the Income Taxes Act of 1918 married women were deemed to be “incapacitated persons” alongside lunatics, idiots and insane persons.

As barriers and disappointments still face women striving to achieve equality and success, it is worth remembering how far we have come. “Rose QC” not only narrates a remarkable life, but gives some perspective to where we are today. It was a different era, one where my mother was denied a pupillage because “Barristers have not got used to women practising at the Bar and sharing Chambers with them and feel some constraint and diffidence when a woman is in chambers”; where women could not enter a court room without wearing a hat; where they could not partake in social gatherings with male barristers because they might be shocked by the conviviality and coarse language; where talking to the Press was professional misconduct; where the timbre of women’s voices was an alleged hindrance to advocacy; and where many solicitors were reluctant to and did not brief female barristers. No equality laws, no sex discrimination laws, no maternity leave or child care facilities existed in those days. It was exclusively a man’s world. Her success in spite of such discouragement, together with the novelty in those days of being a working mother and wife, captured the public imagination leading to widespread national and international press coverage and her consequent fame. She thus became a role model for many women.

The world has fortunately moved on, but some of the old problems still persist for women. What had been only aspirations in those days are now justly expectations: what was novel is now mainstream. A centenary may be a time to take stock. It is therefore heartening to read the roll call of female successes from all over the world appearing regularly in ArbitralWomen News and the ever increasing number of successful female legal practitioners not only in the arbitral world but also in other areas of law. Long may it continue.

Hilary Heilbron QC, Barrister and International Arbitrator, Brick Court Chambers, London